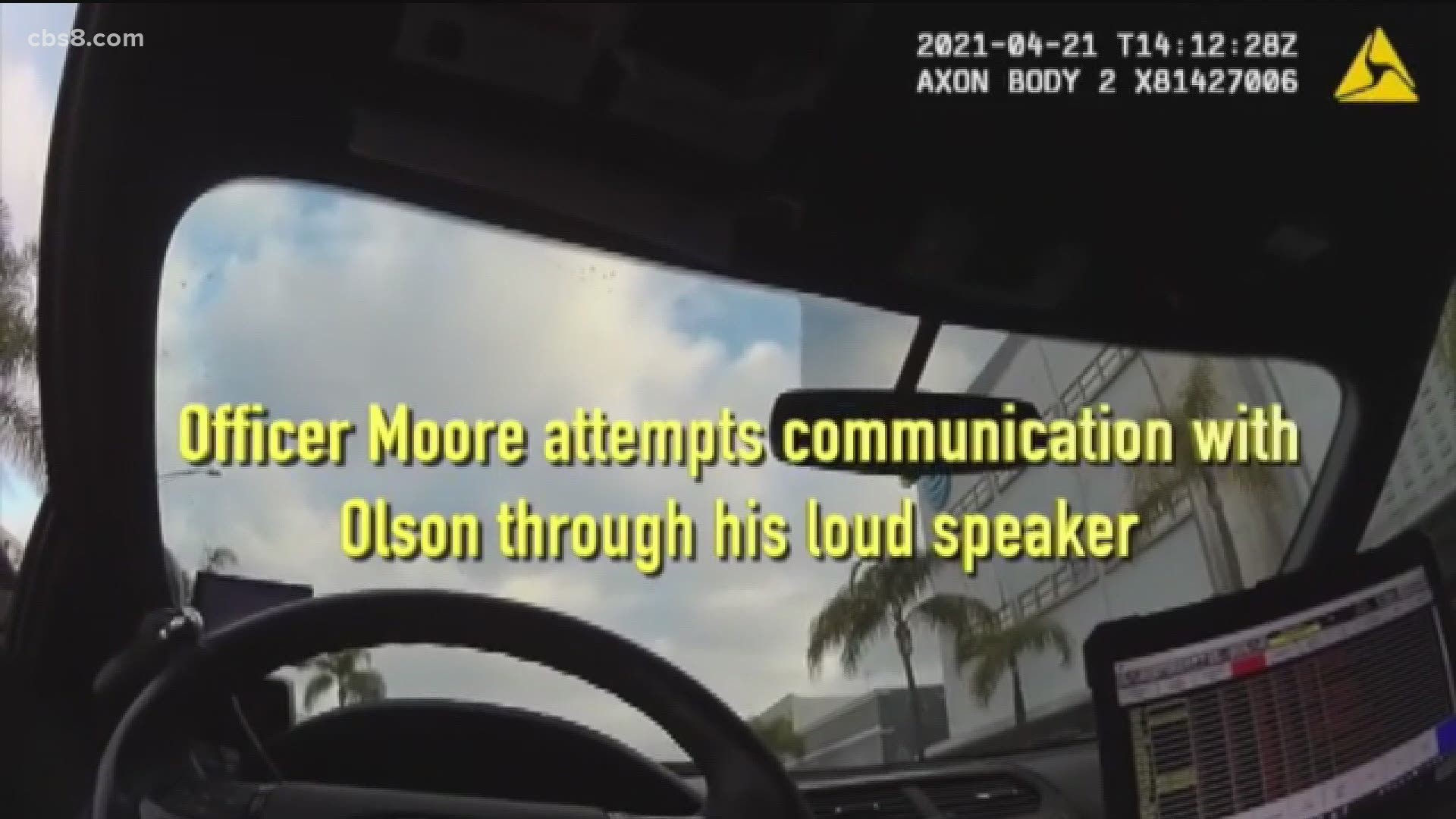

SAN DIEGO COUNTY, Calif. — Escondido Police Officer Chad Moore’s body camera recorded the moments he shot and killed homeless resident Steven Olson in Escondido the morning of April 21, 2021.

The public got a chance to view that footage eight days later when a video about the incident was posted to the City of Escondido’s YouTube channel.

There you can see Officer Moore approach Olson, who was carrying metal objects, and point his gun at him. Olson walked toward him for a few feet while the officer told him to get back.

“I’m going to shoot you,” Officer Moore yelled. Olson continued walking.

It was shortly after that the officer fired seven rounds at Olson, dropping to the ground.

The shooting is visible to the world, but the world can also see Olson’s body blurred right before the shooting, standups and voiceover by Escondido Police Chief Ed Varso and Lt. Kevin Toth, graphic maps of the intersection where Olson was shot, a first responder dispatch recording of residents reporting Olson to law enforcement and security camera footage of Olson walking through the neighborhood.

The Escondido Police Department edited the body-worn footage of its officer shooting Steven Olson. It decided which segments of the footage to show and what to redact.

This brings up questions about framing and why a government agency would package evidence the way it does.

So how can the police edit body-worn camera footage before releasing it to the public?

It’s department policy that Escondido officers have their body-worn cameras on at all times, unless they aren’t on patrol or are alone in their car. There are also federal guidelines that provide blueprints for local agencies who chose to use body-worn cameras.

According to California Western School of Law Professor Gary Gibson, there isn’t really much dictating how law enforcement should edit their video, if at all, before publishing.

“There’s some bare minimum laws,” Gibson said, who’s also a criminal defense attorney with David Silldorf Law. “The departments can get away with just about whatever they choose to do as long as they’re acting within those bare minimum laws.”

Body-worn camera footage falls under an exemption in section 62.54 of the California Public Records Act. This means until an investigation or litigation is complete, the department does not have to release the full video.

“The short answer is police can edit a video in any way they choose and not release sections they believe would compromise the investigation until a certain period of time has passed,” Gibson said.

When the time comes for a department to release video, Gibson said law enforcement can put as many layers of voiceover and graphics as they want on body-worn camera footage as long as they aren’t manipulating the public’s view of what really happened. He said anything that veers from the truth could lead to “consequences in court sooner or later.”

“It’s perfectly permissible for the department to do that[edit footage],” Gibson said. “Every individual community is going to have individual policies and procedures.”

For how law enforcement interprets this, it really depends on which agency you look to.

Chief Varso with EPD told News 8 that the department is not trying to set a positive agenda through their edits, but rather push content toward the truth.

“It’s more than just sharing raw body cam footage,” Chief Varso said. “It’s about sharing what we know.”

In the video produced by the department, Chief Varso said they have a team of law enforcement employees with journalism and video production backgrounds producing it, but he has ultimate editorial call.

When asked about the decision to blur the body of Steven Olson, Chief Varso said it was a “judgment call.”

“This is a difficult area because as law enforcement, we have an obligation to be transparent but I think we also have an obligation to realize you’re watching the last seconds of a person’s life,” he said.

The chief also said he made the editorial decision on having Lt. Toth state Olson's previous crimes and convictions right after viewers saw him get shot.

“It’s relevant to share background that helps the community see what our officers were up against and it helps explain the details of the event," Chief Varso said.

After listing off the crimes, Chief Varso said on the video that he did not "share this to vilify him."

The chief then described how Olson was a product of a system that pushed him in and out of criminal convictions, rather than giving him the help he needed.

"Commentary from me on the need for us as a community to really start discussing some of the flaws we have in our system that creates this revolving door that we don't start talking about until it has some sort of awful ending," Chief Varso said.

Why are some body-cam videos released sooner than others?

The shooting of Steven Olson was released in eight days, swift compared to other body-worn camera footages that took weeks or months to release.

There were protests throughout North County demanding the release of bodycam footage. Chief Varso said it was released swiftly in an effort to increase transparency with the public.

"If we’re not sharing the accurate information of what actually happened, then that leaves room for a rumor to take hold that just isn’t factual," Chief Varso said.

Gibson told News 8 that law enforcement agencies usually withhold the footage as long as they can or release it as soon as possible based on the severity or complexity of the incident.

"A Police department can extend the period of time for up to a year until they have to meet high burden for not disclosing," Gibson said.

Agencies legally have 45 days to release bodycam videos, but they can push it off every 30 days given they can prove releasing it will hurt the case more than help.

They can do that for up to a year.

It's also expensive to store and maintain body-worn camera footage.

The price for bodycam maintenance for the City of Escondido is not listed specifically in the city's budget, but Chief Varso said it was around $80,000 for storage alone.

The laws surrounding releasing or editing bodycam footage, as Gary Gibson would say, are "bare minimum."

The public also only sees a small fraction of the body-worn camera footage out there. With only a fraction of police encounters requiring an investigation and terabytes of data stored from each department's body cams, we are seeing a pinhole in the world of police surveillance.

But both Gibson and Chief Varso agree that body cam footage can be tools to bring the police and general public closer together.

Chief Varso said he acknowledges the distrust in law enforcement, and how examples of bad police practice can ruin his transparency efforts.

“Law enforcement is under a lot of scrutiny and we are continuously trying to find ways to bridge those gaps," Chief Varso said.

“Body-worns overall have been a real positive for the community and a positive for policing but both sides are learning how to use them and how they work and what they should do with them,” Gibson said.

WATCH: Escondido police release video of fatal shooting of man by officer