LA JOLLA (CNS) - Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute announced Monday they have found a way to tether HIV-fighting antibodies to immune cells, creating a cell population resistant to the virus.

Their experiments under lab conditions show that the resistant cells can quickly replace diseased cells, potentially curing the disease in a person with the virus that causes AIDS, according to TSRI.

"This protection would be long-term," said Jia Xie, senior staff scientist at TSRI and one of the authors of the study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers plan to collaborate with investigators at City of Hope's Center for Gene Therapy to evaluate and test the new therapy, as required by federal regulations, prior to testing in patients.

"City of Hope currently has active clinical trials of gene therapy for AIDS using blood stem cell transplantation, and this experience will be applied to the task of bringing this discovery to the clinic," said Dr. John A. Zaia, director of the Center for Gene Therapy in the Hematological Malignancy and Stem Cell Transplantation Institute at City of Hope.

"The ultimate goal will be the control of HIV in patients with AIDS without the need for other medications," Zaia said.

Dr. Richard Lerner, the study's senior author, said the TSRI researchers "are honored to be able to collaborate with physicians and scientists at City of Hope, whose expertise in transplantation in HIV patients should hopefully allow this therapy to be used in people."

According to TSRI, the new technique "offers a significant advantage over therapies where antibodies float freely in the bloodstream at a relatively low concentration. Instead, antibodies in the new study hang on to a cell's surface, blocking HIV from accessing a crucial cell receptor and spreading infection."

Zie, calling it "the neighbor effect," said an antibody stuck nearby is more effective than having many antibodies floating throughout the bloodstream.

Before testing their system against HIV, the TSRI scientists used rhinovirus, which is responsible for many cases of the common cold, as a model.

They used a vector called lentivirus to deliver a new gene that instructed cultured human cells to synthesize antibodies that bind with the human cell receptor (ICAM-1) that rhinovirus needs. With the antibodies monopolizing that site, the virus cannot enter the cell to spread infection, according to the researchers.

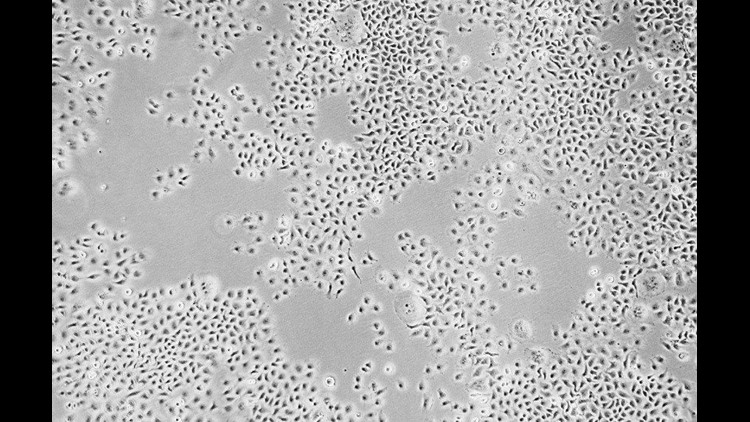

Because the delivery system cannot reach 100 percent of cells, the finished product was a mix of engineered and unengineered cells. The researchers then added rhinovirus to the cell populations and waited to see what would happen and observed that the vast majority of cells died in about two days.

In dishes with only unengineered cells, the population never recovered. There was an initial die-off in the mixed engineered/unengineered populations, also, but their numbers quickly bounced back. After 125 hours, those cell populations were back up to around the same levels as cells in an undiseased control group.

"In essence, the researchers had forced the cells to compete in Darwinian, `survival-of-the-fittest' selection in a lab dish," according to TSRI. "Cells without antibody protection died off, leaving protected cells to survive and multiply, passing on the protective gene to new cells."

The researchers then used the same technique against HIV, knowing that to infect a person, all strains of the virus need to bind with a cell surface receptor called CD4. They tested antibodies that could potentially protect the receptor on the very immune cells normally killed by HIV, and the technique worked, Lerner said.

"This research is possible because of the ability to select specialized antibodies from combinatorial antibody libraries," he said.

After introducing cells to the virus, the researchers ended up with an HIV-resistant population. The antibodies recognized the CD4 binding site, blocking HIV from getting to the receptor, according to TSRI.

The scientists further confirmed that tethered antibodies blocked HIV more effectively than free-floating, soluble antibodies in experiments led by two study co-authors, including Devin Sok of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative.

In addition to potentially collaborating with City of Hope, Xie said the next step in the research is to try engineering antibodies to protect a different receptor on the cell surface.

Dr. Joseph Alvarnas, director of Value-Based Analytics at City of Hope, said the TSRI technique could help patients, who -- despite treatment with anti- retroviral drugs -- still suffer from higher rates of diseases, such as cancers.

"HIV is treatable but not curable--this remains a disease that causes a lot of suffering. That makes the case for why these technologies are so important," he said.