CALIFORNIA, USA — This story was originally published by CalMatters.

In September 2020, workers in Brawley near the Mexico border began loading dump trucks with soil from the site of an old pesticide company. As an excavator carefully placed the Imperial County waste into the vehicles, a worker sprayed the pile with a hose, state records show. Another was on hand to watch for any sign of dust. The trucks then drove through a wash station that showered dirt off the wheels and collected the runoff water.

There was a reason for such caution. Shipping documents indicate the soil was contaminated with DDT, an insecticide the federal Environmental Protection Agency banned decades ago and that research has linked to premature births, cancer and environmental harms. The Brawley dirt was so toxic to California, state regulation labeled it a hazardous waste. That meant it would need to go to a disposal facility specially designed to handle dangerous material – a site with more precautions than a regular landfill to make sure the contaminants couldn’t leach into groundwater or pollute the air.

At least, that would have been the requirement if the waste stayed in California. But it didn’t.

Instead, the trucks – carrying nearly 1,500 tons of California hazardous waste – rumbled just over the Arizona border to the La Paz County Landfill, a municipal solid waste dump several miles from the Colorado River Indian Tribes’ reservation.

The journey is a familiar one for California’s toxics. Since 2010, nearly half of California’s hazardous waste has left the Golden State, according to figures the state released last summer.

Some of this estimated 10 million tons has gone to specialized facilities, but California government agencies and businesses have also transported much of it over the border to states with weaker environmental regulations and dumped it at regular municipal waste landfills, a CalMatters investigation has found. These are cheaper alternatives with more limited protections and oversight than sites permitted to handle hazardous waste. A CalMatters analysis of state shipping records shows that two of the most heavily used by California are near Native American reservations – including a landfill with a spotty environmental record.

While there is nothing illegal about the practice, critics contend it raises troubling questions for a state that loves to pat itself on the back as an environmental leader and a shining example of how to protect the planet.

“California shouldn’t have stringent laws and then send this waste out of state. How is that fair?” said Cynthia Babich, an environmental advocate who was on a state advisory committee several years ago looking at hazardous waste. “You’re just shifting the burden. It’s really not addressing the problem.”

CalMatters spent four months examining how California handles its hazardous waste – analyzing state and federal databases with millions of shipping records, reviewing regulatory filings and archival documents, obtaining hundreds of pages of environmental inspection reports for waste disposal facilities in Arizona and Utah, and interviewing regulators, environmental advocates, engineers and waste industry sources.

CalMatters found no reports directly linking California waste to public health issues or pollution in surrounding communities. But environmental analyses at and around these out-of-state landfills are, at best, limited – largely relying on self-reported data from the waste companies. One Arizona landfill doesn’t conduct groundwater monitoring.

The waste leaving California includes asbestos, treated wood and auto shredder detritus. But the biggest source is contaminated soil – the product of California’s massive efforts to right decades of environmental harm and restore the land at the site of old factories, refineries and military installations. This is soil contaminated with heavy metals such as lead and nickel, petroleum hydrocarbons, and chemicals including DDT. The soil largely comes from cleanups that government agencies either oversee or directly manage.

In the past five years, California has disposed of more than 660,000 tons of contaminated soil in Arizona landfills and nearly a million tons at a Utah landfill, according to data in a state tracking system. That includes hazardous waste from the Mission Bay redevelopment in San Francisco, military base cleanups in San Diego and transportation authority projects in San Bernardino County.

At least one business hopes there will be more. A company in Utah is currently trying to get a permit in that state to open a landfill right on the edge of the Great Salt Lake and planning to take – among other waste streams – contaminated soil. An economic analysis the company filed with Utah regulators says there’s a “unique market opportunity created by California law.”

And while California officials have discussed the issue for years, including a state initiative that looked at ways to treat more contaminated soil on-site, they’ve done little to address it. In fact, the state’s own hazardous waste watchdog – the Department of Toxic Substances Control – is one of the biggest out-of-state dumpers. That’s despite a 1991 pledge signed by then-Gov. Pete Wilson to keep California waste in California.

Since 2018, the department has removed more than 105,000 tons of contaminated soil from the site of the state’s biggest cleanup effort – the area around the old Exide battery recycling plant in Los Angeles County – and disposed of it in western Arizona. Regulatory filings show most wound up at the South Yuma County Landfill, which sits just a few miles from the Cocopah Indian Tribe’s reservation and abuts the lush, green orchards of a company that grows organic dates. It’s a landfill that the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality labeled as posing an “imminent and substantial threat” in 2021 after an inspection noted windblown litter, large amounts of “disease vectors” (flies and birds), and groundwater with elevated levels of chromium – a metal that can harm people and the environment.

Officials with the Department of Toxic Substances Control said the decision to ship the waste out-of-state was driven by cost. Director Meredith Williams acknowledged her agency doesn’t monitor landfill conditions in other states. But she said the department is crafting a new hazardous waste management plan for the state – due in 2025 – that could “reflect the kinds of concerns that you’re hearing about.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Some waste industry experts contend there’s little risk to people or the environment from the contaminated dirt. They say California regulations are too strict – labeling some waste as hazardous under state law even though it falls below the federal threshold to be considered hazardous. They say modern landfills here and out-of-state are more than equipped to handle the cleanup waste, particularly because contaminants such as heavy metals don’t migrate well through soil. They contend the regulations are therefore driving up disposal costs for businesses and the government, and also carry an unintended environmental cost – creating needless emissions from the thousands of trucks and train cars transporting the waste out of state each year.

That’s little comfort to people like David Harper, a member of the Colorado River Indian Tribes whose reservation is near the La Paz County Landfill. That’s a landfill where California agencies and businesses sent more than 160,000 tons of contaminated soil since 2018, including the DDT contaminated waste from Brawley, the state’s waste tracking system shows.

“If it was not a problem, why didn’t they keep it themselves? Why does it have to come here?” Harper said. “Why isn’t it in California?”

California’s magical border

Drive an hour east of Joshua Tree National Park and you’ll hit the Colorado River Indian Tribes’ reservation — nearly 300,000 acres of land straddling the Colorado River, the natural border between California and Arizona.

A funny thing happens at that border. Soil contaminated with enough heavy metals like lead, or chemicals like DDT, that it would be regulated as a hazardous waste in California suddenly turns into little more than a pile of regular, old dirt. This alchemy (and no, nothing actually changes in the soil as it crosses the border) has to do with patchwork regulations and interstate commerce.

Congress enacted the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act in 1976. This federal law defines what counts as a hazardous waste nationwide and lays out how such waste needs to be handled. A separate law enacted around the same time governs disposal of chemicals such as PCBs. If a lab determines that a waste is hazardous under federal law, then it needs to be treated, stored or disposed of at a facility specially permitted to handle hazardous waste.

But the federal law acts as a baseline. Some states, including California, have enacted their own more stringent environmental laws and regulations. Gov. Jerry Brown signed the Hazardous Waste Control Act in 1972, defining hazardous waste under California law. Subsequent laws and rulemaking expanded the state’s reach.

California has also adopted its own testing requirements. Both federal- and state-required lab tests essentially try to mimic landfill conditions to see how much of a contaminant might leach into groundwater. The tests vary in terms of how long they last, the amount of dilution and the acid used.

So even if a waste doesn’t meet the threshold to be considered a hazardous waste under federal law, it can be considered hazardous under California’s different testing system and requirements. Such waste is sometimes called “California hazardous waste.”

From 2010 through mid-last year, California generated about 17 million tons of waste considered hazardous only under state law compared to about 3.8 million tons of waste that met the federal definition of hazardous, according to figures from the state. More than a third of the California-only hazardous waste was contaminated soil.

California hazardous waste generally needs to be treated as toxic in the state and disposed of at facilities authorized to handle such materials.

Such sites are subject to increased state and federal oversight and design requirements. For example, a hazardous waste disposal facility needs to have a double liner system, essentially making it harder for toxic material to seep out of the landfill and into the surrounding area. A regular landfill isn’t required to have two of those protective barriers, experts told CalMatters.

California has only two hazardous waste landfills: the Kettleman Hills Facility in Kings County and the Buttonwillow landfill facility in Kern County.

Officials in the Department of Toxic Substances Control initially told CalMatters that capacity could be a barrier to disposal at these two California sites. But they could not provide any examples where space considerations had driven a decision to export waste instead.

Jennifer Andrews, a spokeswoman for WM (formerly known as Waste Management Inc.), which operates the Kettleman Hills facility, said the site “has enough capacity to meet the State of California’s hazardous waste disposal needs.”

“We also have plenty of space to meet the needs of DTSC waste for years to come, providing the agency permits new disposal units at our site.”

Buttonwillow, whose representatives didn’t respond to an interview request, also appears to have enough room to take contaminated soil – with about 5.5 million cubic yards of remaining space, according to corporate filings.

But the two sites have faced their own scrutiny over regulatory lapses and environmental concerns, including a chemical spill at Buttonwillow years ago and the mishandling of some toxic waste at Kettleman Hills that resulted in government fines for each. State regulators have cited both for numerous violations over the years, Department of Toxic Substances Control records show. And while environmental activists have said they don’t want waste going to out-of-state landfills, some also don’t want California’s hazardous waste going to those two in-state facilities near low-income communities of color.

Cost appears to be a major factor in determining where California-only hazardous waste ends up. The Department of Toxic Substances Control provided figures to CalMatters showing the cost to dispose of California-only hazardous waste in-state can be about 40% to 60% higher than out-of-state disposal. Reasons include fees, taxes and “time at landfill for disposal (i.e., long wait times), and scheduling difficulty due to large volumes of hazardous waste for disposals,” according to the department. Other estimates put the cost at about 20% more, depending on where in the state the waste is generated.

Last year, state parks officials needed to dispose of 2,300 tons of soil workers excavated from the site of the Los Angeles State Historic Park in California – an old railyard. Ultimately, the soil – listed in shipping records as “Impacted with metals” – was transported just over the river to the La Paz County Landfill outside of Parker, Arizona, shipping records show.

“The environmental consultant hired by State Parks selected the La Paz facility as it was the most economical, at roughly half the cost, and most reliable choice, while also meeting all required environmental standards,” according to a written statement from the parks department.

The parks department also said California’s two hazardous waste landfills “do not always accept certain hazardous wastes due to various factors such as capacity or technical issues. They also typically require a more lengthy and burdensome approval process.”

The decision was certainly not unique. Since 2010, about 43% of California-only hazardous waste has been transported out of the state – much of it to Arizona and Utah landfills, government records show.

California regulations may stop at the border, but its waste does not.

Sacred ground

On a clear morning shortly after Thanksgiving, David Harper took a CalMatters reporter and photographer on a tour of the area around the La Paz County, Arizona, landfill. Harper is a member of the Colorado River Indian Tribes and a former chairman of the Mohave Elders Committee. He is also a founding board member of Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice, an environmental advocacy organization that has long opposed California’s out-of-state dumping.

The reservation sits inside a valley about five miles from the landfill at its closest point. It’s a dusty landscape two-and-a-half hours west of Phoenix that smells of creosote bushes and is dotted with saguaro, the tall cactus symbolic of the American West.

Mountains border the area, each a part of the Mohave creation story. Redtail Hawk Mountain, Moon Mountain, Fishtail Mountain. Harper calls one range Old Woman and says his people believe the creator turned a revered member of the tribe into a mountain so she could forever oversee the land – her nose, chin and bosom silhouetted against the blue expanse of sky.

“It’s a living, breathing environment. But to you, it’s a desert wasteland. But it’s not to us,” Harper said. “These areas are sacred.”

Some liken the area to the land along the River Nile, said Valerie Welsh-Tahbo, director of the Colorado River Indian Tribes Museum and a former tribal council member. The river cutting through the desert landscape creates rich soil for farming melons, cotton and alfalfa, she said.

Like some other tribal members interviewed for this story, she worried about the California hazardous waste transported to the landfill just outside the reservation.

“I don’t think enough people are aware that that’s happening, for one thing, and what kind of toxic materials are being dumped out there,” Welsh-Tahbo said. “I think the general thinking is, ‘Well, it’s far enough away from the municipalities that it should be okay.’ So, I guess out of sight, out of mind seems to be the attitude.”

Landfills like the one in La Paz are subject to limited oversight. The federal EPA doesn’t routinely monitor conditions there. The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality does inspect municipal solid waste landfills though there is no requirement as to how often. The goal is annually, a department official told CalMatters. The department inspected the La Paz facility in October 2021 and identified no deficiencies, according to a copy of the inspection report the department provided CalMatters.

Such reviews, however, are not necessarily comprehensive. For example, the department typically doesn’t do its own water testing, a state spokeswoman confirmed, instead relying on landfills to test for contamination and to report the results accurately. But even then, there are gaps.

The La Paz facility obtained an exemption allowing smaller landfills to avoid certain requirements like groundwater monitoring. That was in 1996. As a result, the landfill hasn’t had to report such water quality test results for more than 25 years and, according to the most recent annual inspection report, doesn’t monitor groundwater at the site.

The operator of the site, Republic Services, said in an email to CalMatters that the landfill has “a state-of-the-art engineered composite liner system,” and that “the depth of the uppermost groundwater aquifer is 460 feet or more below the bottom-most liner.”

Republic Services is “committed to safety, environmental responsibility, sustainable solutions, and ensuring that all our facilities comply with federal, state and local laws and regulations,” according to the company’s statement to CalMatters.

Caroline Oppleman, a spokesperson for the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, said in an email to CalMatters that “landfills are very closely regulated” under federal and state law. She said this includes oversight on “where they can be built, how they are built, waste they can accept, and finally, how they are closed and monitored for a minimum period of 30 years after closure.”

Indeed, some engineering experts say regular landfills are more than equipped to safely dispose of California’s contaminated soil, with or without the extra safety features of a permitted hazardous waste facility. Modern landfills are well designed, and composite liners have a remarkable record when it comes to containing waste, said Craig H. Benson, a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin and national expert on waste facility design. It’s not like the 1980s when a landfill could be little more than a hole in the ground, he said.

And, even something as scary sounding as DDT doesn’t tend to migrate too far through the ground, he added.

“Those types of compounds are pretty immobile,” Benson said. “You wouldn’t want to be eating them.”

As a result, engineers CalMatters spoke with said California’s current regulatory system can be overkill – creating an unintended environmental impact from the greenhouse gas emissions of all the trucks and trains carrying the waste out of state when California could safely dispose of the contaminated soil in regular landfills in its own state.

“Does that make any sense at all with all the diesel emissions, safety issues, the risks from actually hauling it there?” Benson said. “I’d much rather put it in a safe and secure landfill that’s maybe 10 miles away.”

Decades of dumping

California hazardous waste has been going to out-of-state facilities for decades. In the late 1980s, the Federal Reserve Bank in San Francisco was sending its shredded money – considered hazardous in California because of the lead content – to a landfill in Jackson County, Oregon, according to memos from Oregon environmental officials at the time.

Oregon regulators in 1988 proposed a rule to effectively stop California from such disposal practices. A company wanted to build an infectious waste incinerator in Klamath County – three miles from the border with California.

“Hazardous waste is more strictly regulated, and therefore, more costly to manage … As a result, some generators of hazardous waste will pursue ways to ship the waste to a neighboring state,” according to a 1988 memo from an Oregon environmental regulator to the state’s Environmental Quality Commission.

“A receiving state is, therefore, at risk of becoming a ‘dumping ground.’”

Oregon ultimately adopted a rule in 1989 that says if another state considers waste to be hazardous, then Oregon will also consider the material to be hazardous even if the waste wouldn’t qualify for such a designation under Oregon’s laws. In other words, if California says contaminated soil is toxic then Oregon treats it as toxic. Nevada has a similar rule.

As a result, those states’ solid waste landfills don’t appear to be “dumping grounds” for California hazardous waste, shipping records indicate. But some of California’s neighbors – notably Utah and Arizona – don’t have such rules.

Environmental activists in the 1990s protested in Arizona about the waste coming from the Golden State.

“This stuff is toxic waste. It is material that can kill you,” said Bradley Angel, executive director of Greenaction, an environmental advocacy organization. “It is material that can cause cancer. That is why it’s called toxic waste.”

“The most vulnerable of our society continue to get dumped on.”

But the areas around the out-of-state landfills are sparsely populated, and some local officials there have welcomed the waste as a vital part of their economy.

Local officials in Utah sent letters in 2017 to their state environmental regulators saying the ECDC landfill in East Carbon was an important source of tax revenue and had “enabled quality jobs to be maintained in rural Utah.” ECDC is a major destination for California’s contaminated soil – much of it transported via rail from cleanup sites and development projects in San Francisco, according to hazardous waste shipping records filed with regulators.

The facility drew regulatory scrutiny years ago, Utah environmental records show. In 2004, Utah regulators learned some waste from a refinery in Wilmington, California – considered hazardous under federal standards – was disposed of at the landfill. In late 2005, workers started excavating that material from the landfill, according to archival documents.

In recent years Utah regulators haven’t identified any issues during inspections.

David Ariotti helped oversee the landfill for years as an engineer in Utah’s Department of Environmental Quality. Now retired, he said the landfill was “better managed than most.” He said regulators knew the types of waste the facility would take, including California-only hazardous waste.

“As with any industry, if there’s money to be made, they’re looking to make it,” Ariotti said. “They met everything they were supposed to. I inspected it and I was satisfied with the construction. They didn’t take any shortcuts.”

He was, however, always concerned about the landfill’s proximity to an aquifer. “I was not in favor of the landfill because of where they put it,” he said, adding that any risk to groundwater is a concern.

In a statement, Republic Services said, “The environmental services industry is one of the most heavily regulated in the United States and in most cases, our Landfills exceed safety standards set by the EPA and state regulatory agencies. This is the case at ECDC,” according to the company, which touted the site’s advanced leak barrier and detection system.

The Utah landfill conducts its own groundwater monitoring and submits the results to the state for review. Those reports in recent years have shown no problems, state regulators said.

Old promises

There was a time when California promised not to discard its toxic waste in other states, regardless of whether those states and communities would allow it.

In 1991, then-Gov. Pete Wilson signed the Western States Regional Waste Management Protocol. He was one of 21 governors to sign the document, which came out of the Western Governors’ Association, according to a copy of the protocol CalMatters obtained from the Colorado State Archives. The agreement was a pledge to “do everything economically and environmentally practical to ensure that wastes generated in our states are treated and disposed of in our own state before resorting to export.”

“Wastesheds, like watersheds, do not follow the political boundaries on a map,” the protocol stated.

California’s Department of Transportation – Caltrans – still adheres to the agreement even though it has long since expired. A Caltrans spokesman told CalMatters such regional protocols typically last for three years and expire unless renewed. The waste agreement was readopted in 1995. The Western Governors Association adopted a related policy resolution in 2003, according to a copy CalTrans provided CalMatters. That resolution didn’t ban waste shipments between states, citing “many examples of safe, effective and efficient cross-border waste management arrangements.”

The resolution did say “each state should do everything it possibly can to deal with its own solid waste in-state, including making those hard siting decisions when no one wants it ‘in their backyard.’”

In an email to CalMatters, Caltrans media relations manager Will Arnold said his department’s “policy is, and has been since 1995, to dispose of hazardous waste generated by highway construction within the state, unless there are exceptional circumstances.”

But the state agency in charge of overseeing hazardous waste in California apparently has no such self-imposed limitation.

The Department of Toxic Substances Control oversees or manages numerous environmental remediation projects around the state. The biggest cleanup is at the site of an old battery recycling facility called Exide in the Los Angeles County community of Vernon. For years, the department has been cleaning up toxic waste on site and in the surrounding neighborhoods, digging up soil littered with lead.

Much of that waste is going to Arizona. The state’s hazardous waste tracking system shows that since 2018, more than 105,000 tons of contaminated soil from the Exide residential cleanup have gone to that state. Some wound up at the La Paz County Landfill. Most, however, went to the South Yuma County Landfill, just outside of Somerton and near the Mexico border, according to the state’s data.

“A cost-analysis determined that savings associated with out-of-state disposal allowed DTSC to cleanup more contaminated residential properties,” according to a statement from the Department of Toxic Substances Control.

The landfill is about three miles from the Cocopah Reservation, federal records show. The site is bordered by lush agricultural fields – a chain link fence and narrow dirt path separate the landfill from a neighboring organic date orchard. (The head of the date farm did not respond to an interview request.)

CalMatters obtained landfill inspection reports for 2020 through 2022 from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. During that period, Arizona inspectors flagged issues in a number of the South Yuma landfill inspections. Some were relatively minor and easily corrected – for instance, not enough fire extinguishers near the area where the landfill stored waste tires.

Others were potentially more concerning. An April 2021 inspection report identified issues with windblown litter, disease vectors like birds and insects, and the system to collect and control stormwater runoff. The inspection also noted elevated chromium levels in one of the monitoring wells on site. In a question on the inspection report asking, “Has any condition or activity resulted in an imminent and substantial threat to public health or the environment?” the box for yes is checked.

As a result, the landfill operator in October 2021 entered into a consent order with the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. In signing the order, the company didn’t admit to wrongdoing but agreed to a number of fixes. The landfill made changes and the department terminated the order in February 2022, regulatory filings show.

Just a few months later, however, Arizona inspectors again identified “potential deficiencies” at the site. Among the issues, inspectors in June again saw windblown litter, flagged the company for not submitting certain reports and noted some groundwater tests exceeded water quality standards, according to a June inspection report.

The landfill “corrected all conditions listed” in the findings, according to an email from Arizona’s Department of Environmental Quality. The department is also “working with them to develop a revised groundwater monitoring plan,” the department said.

The company declined to give CalMatters a tour of its facility. (“Sorry. But no,” a company official texted in response to a reporter’s request.) A company representative did provide written responses to questions indicating the company, which bought the landfill more than 12 years ago, “hired the best engineers we knew in Southern CA to review the permits and substantiate the operations.”

According to the response, the elevated chromium noted in the April 2021 inspection “has not been repeated in subsequent groundwater monitoring events.”

The company “maintains a 100-foot setback from all adjacent properties and public right of ways for all waste disposal activities. California waste traffic approaches the landfill from a public road and enters from a point of access as far as possible from neighboring farms and after checking in and initial screening, directed to the landfill working face where it is landfilled and daily covered with earthen material,” according to the company.

The response also indicated windblown litter is a common problem at municipal solid waste landfills and that the company has filed all required notices and reports with state regulators.

The recent regulatory issues don’t appear to have impacted the flow of waste from California to the South Yuma landfill. Since the April 2021 inspection, the landfill has gotten more than 1,800 shipments of contaminated soil from the Exide cleanup, the state’s waste tracking system shows.

Asked if it’s safe to dump California-only hazardous waste at a municipal solid waste landfill like South Yuma, the director of California’s Department of Toxic Substances Control, Meredith Williams, said she couldn’t “make a blanket statement about the safety of that because everything’s so situational.”

“What is the hazard? Why is it classified as hazardous, non-hazardous waste? What are the conditions that are relevant and how well is …that out-of-state landfill managed?” she said.

Her department doesn’t appear to know how such landfills are managed or their safety track records. The department doesn’t routinely get inspection records nor does the agency monitor out-of-state facilities, Williams said.

“We have our hands full enough,” Williams said. “I think we’re not in a position to go out of state and assess an out-of-state landfill for its operations. It’s more than we can take on.”

Lots of talk

In 2015, the Department of Toxic Substances Control got money from the state for an initiative to reduce the amount of hazardous waste generated in California. The state had recently approved the expansion of one of California’s two hazardous waste landfills but officials were concerned the communities around those landfills bore a “disproportionate burden” for disposal of toxic waste in the state, agency records show.

That led to the creation of a special advisory committee made up of members representing a diverse cross section of interests including the waste industry, environmental advocates and academic researchers.

One of the main areas the panel looked at was contaminated soil. That’s because in 2015, soil from cleanup sites was the single biggest type of hazardous waste generated in California, according to a report of the group’s findings.

The committee talked about the fact the soil was often going to landfills in other states, members told CalMatters.

“We didn’t want to be shipping California’s risk factors to other people’s backyards,” said Oladele Ogunseitan, a microbiologist and presidential chair at the University of California, Irvine, who was on the committee. The panel didn’t explore what happens to the waste out of state, he added.

“We hope they know what they’re doing,” Ogunseitan said. “These things don’t know state boundaries.”

Ogunseitan said he understood the engineering of landfills has changed over the years and that modern designs are more protective. But little risk is not the same as no risk, he said, and contaminants can be a danger generations from now.

“If I lived in Arizona I’d be out protesting,” he said.

Cynthia Babich was also on the committee. Babich is director of the Del Amo Action Committee, an environmental justice organization that formed in response to community concern over Superfund sites in Los Angeles County. She said the advisory panel looked at various alternatives to excavating soil and dumping it at landfills. These were technologies to treat contaminated soil on site.

Among the technologies discussed was something called “soil washing,” in which dirt contaminated with metals was scrubbed to remove the toxic material, the committee’s report shows. Another involved the use of heat to destroy certain contaminants.

At the time there were questions about the cost and effectiveness of such technologies. The Department of Toxic Substances Control ultimately released a 2017 report based on the committee’s findings. That report, among other things, recommended more research into technologies for treating contaminated soil.

But the state didn’t follow through, citing a lack of money.

“Now we have a report and nothing happened,” Babich said.

Babich said her group wants the state to clean up contamination that has long burdened lower-income communities of color. But simply dumping the waste on another marginalized community is not the answer.

Williams, the department’s director, acknowledged the original vision was for pilot projects to study alternatives to excavation.

“However, there was no appropriation that was given to support those pilots. And so there was no place to take the recommendations and continue to act,” she said.

Officials are once again taking a close look at how the state handles its toxic materials and could make changes. The review is part of a 2021 law that, among other things, is requiring the state to prepare a hazardous waste management plan.

As part of the planning process, the department is scheduled to release a detailed public report with data on hazardous waste California is generating and where it’s going by March 1. The actual management plan, however, isn’t due until March 2025.

Next up: The Great Salt Lake

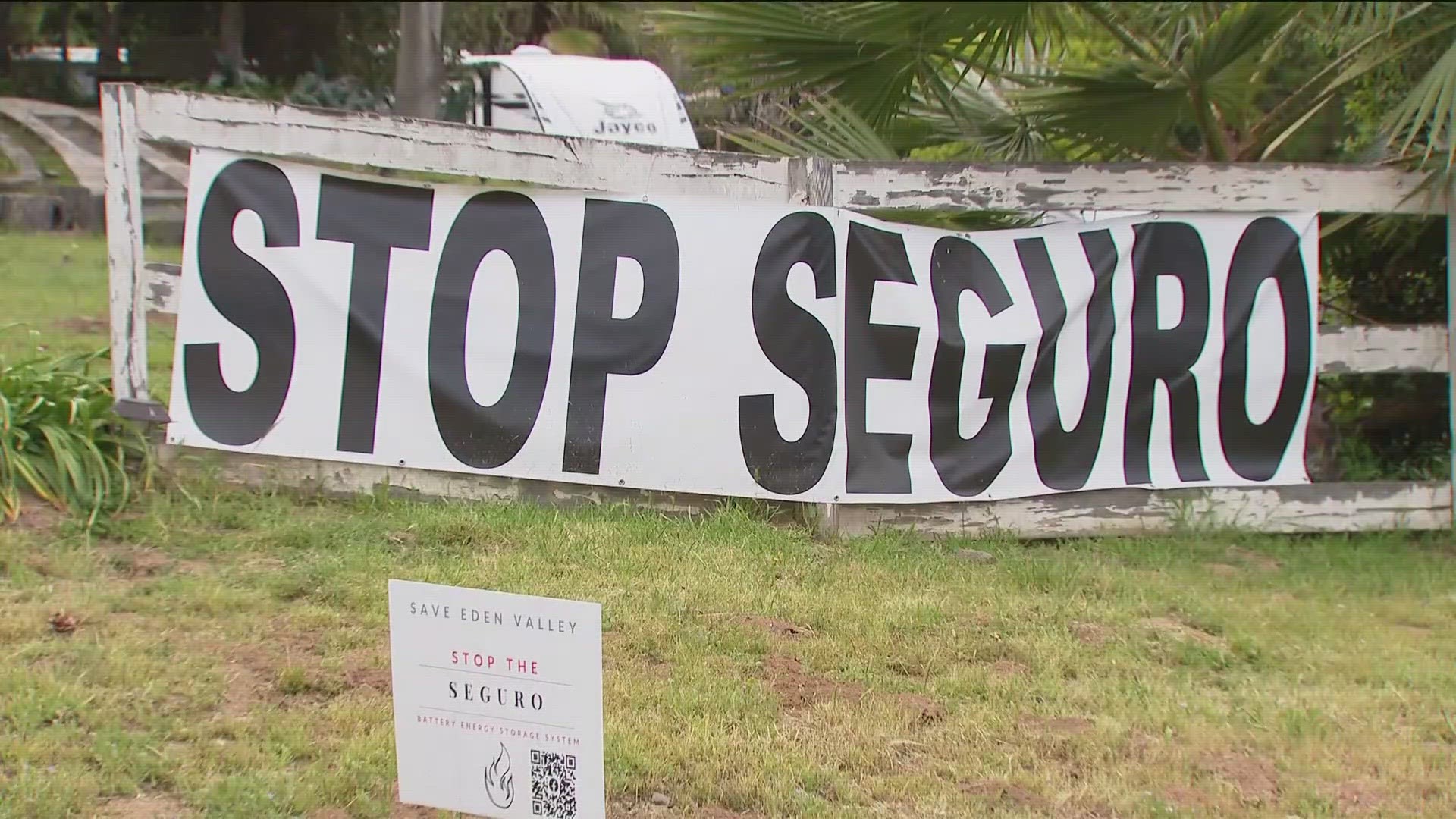

One company appears to be banking on the continued flow of California hazardous waste. A company called Promontory Point Resources is currently trying to get a permit from Utah regulators to operate a landfill that could take out-of-state waste, including contaminated soil from California.

The company behind the Promontory Point project had a needs assessment prepared as part of its permit application. That analysis calls excavated soil a “unique market opportunity” and suggests many Northern California hazardous waste generators would send their contaminated soil to the landfill because of the low cost. The analysis estimates the cost to send contaminated soil from northern California to the Promontory Point facility would be $100 per ton as compared to $145 per ton at the Kettleman Hills hazardous waste disposal facility.

The proposed landfill sits on the tip of Promontory Point, a peninsula jutting down into the Great Salt Lake. The facility is roughly half a mile from the edge of the lake and accessible from Ogden via a bumpy railroad causeway. The drive yields expansive views of the surrounding mountains and, on a recent visit, the sight of an eagle perched atop a wooden utility pole.

“It’s very problematic,” said Lynn de Freitas, executive director of FRIENDS of Great Salt Lake, one of the groups opposing the landfill. She said the area is important for “migratory bird habitat, brine shrimp” and the overall health of the saline system.

Compass Minerals, a company with facilities near the landfill, has also raised concerns. The company uses brine from the lake to produce minerals for fertilizers used in fruit, tree nut and vegetable crops.

Early soil borings in the area found fractured bedrock, said Joe Havasi, Compass Minerals’ vice president of natural resources. Such fractures could be a path for contaminants from the landfill to “flow quickly and efficiently to the lake,” Havasi said. The scale and extent of such fractures hasn’t been fully assessed and there should at the very least be more testing before any permit approval, he added.

In a written response to questions from CalMatters, the Utah Department of Environmental Quality wrote that “there are no concerns with the bedrock beneath the landfill.”

As to whether the department has any concerns about the type of waste that could be dumped on the lake’s edge, the agency responded that the “landfill permit application is currently under review.”

Landfill representatives did not respond to multiple interview requests.

If Utah does approve the permit, Lynn de Freitas, the environmental advocate, has a plea to California.

“You could hold on to your own waste,” she said. “That would be ideal.”