TOKELAND, Wash. — Blue tsunami evacuation route signs are now a common sight on the shores of America’s west coast states. The idea is to get to higher ground, but that depends on a lot of factors.

If you can’t get out of harm’s way fast enough, vertical evacuation structures could be a lifesaving option.

Tsunamis are generated from around the Pacific Rim and can strike California, Oregon, and Washington from afar. The damage and fatalities suffered could be reminiscent of the magnitude 9.2 Alaska earthquake in 1964.

If the tsunami is generated by a local quake along the Cascadia Subduction Zone, there may not be an undamaged, uncluttered, and uncrowded road or enough time to get out of the tsunami’s broad path. Emergency managers warn people on the coast could have as little as 10 to 15 minutes to get high enough once the earthquake has stopped shaking.

But what if you could stay put and ride the tsunami out?

One of the solutions is vertical evacuation, and tsunami-prone Japan has had them for decades. It can consist of a super strong building tall enough to stay above tsunami waves, such as a tower with platforms to hold hundreds or an earthen berm with enough height and armoring to prevent waves from eroding away the structure.

Washington state has the first vertical evacuation structure in North America at the Ocosta School District near Westport, Wash.

Residents paid for the tower themselves through a school bond issue. The school it replaced was due to be torn down. The additional cost to make it a tsunami ready structure added about 20% to the cost. The result is a structure that can hold the line against the onslaught of debris-filled waves with an easily accessible roof high in the air. It also doubles as the school gym, cafeteria and classrooms.

Students in the Ocosta School District, which houses an elementary and junior and high school on one site, practice drills regularly to get up large stairways in the corners of what otherwise looks like a new school. Below, walls are designed to give way under the pressure of the waves, allowing the stout stairways to stand against the punishing flow of water and floating debris.

It’s also available to the community for evacuation. When you look at the doors, the opening bars aren’t on the inside of the building to get out, they are on the outside of the building to allow people to quickly get in and up.

The Ocosta School District is one model for a vertical evacuation structure; it’s what’s often referred to as dual use.

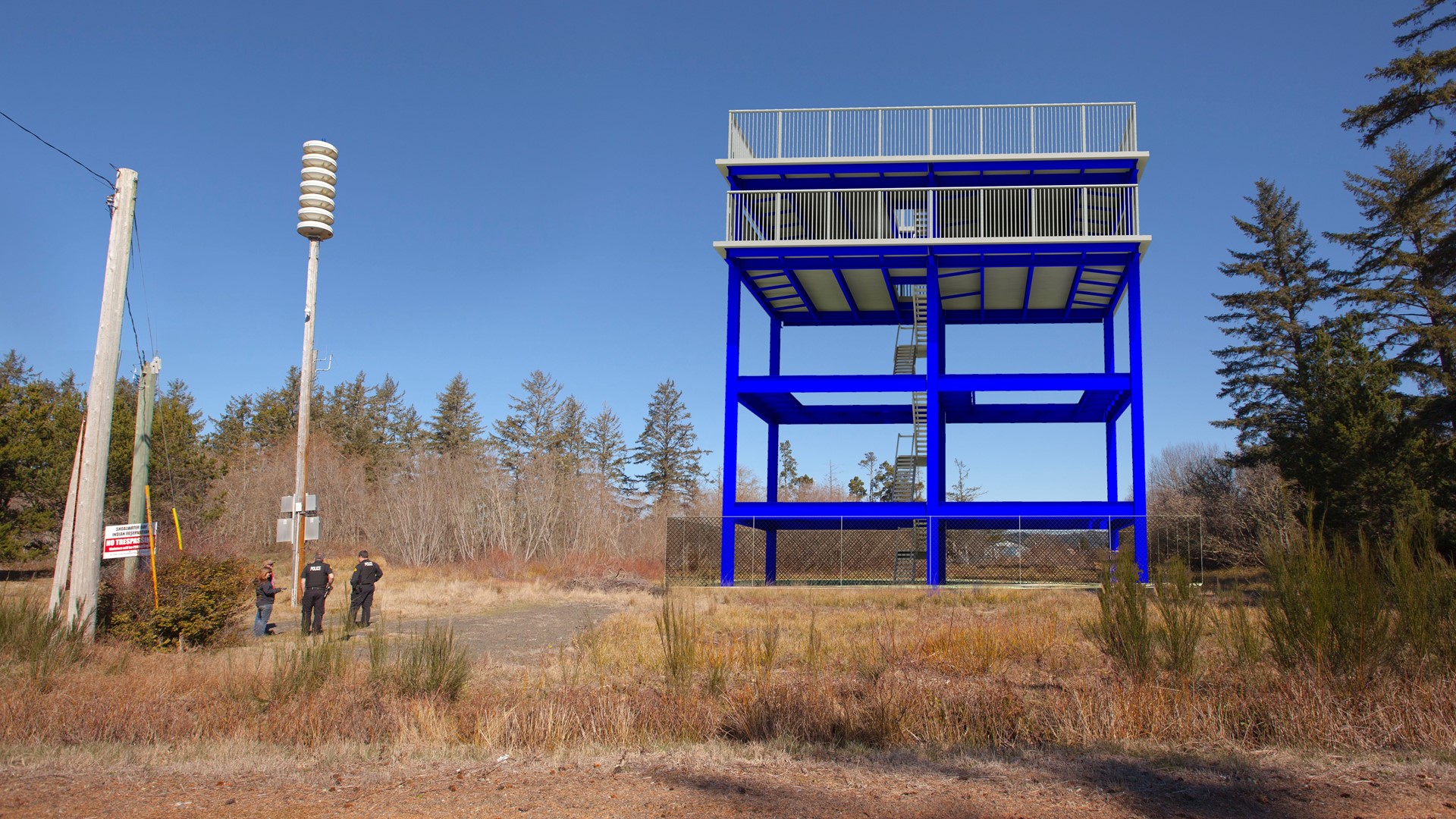

Twenty miles south on the Shoalwater Bay Indian Reservation, a second structure is progressing quickly to erect an evacuation tower capable of holding 600 people.

“Our people deserve to be safe; they deserve to have hope,” said Lee Shipman, the tribe’s emergency management director.

The tower is located just inside the tribe’s property line, so it can be shared with the non-tribal residents of Tokeland, Wash. Region 10 of the Federal Emergency Management Agency administered a grant covering more than $2 million of the estimated $2.5 million cost of design and construction. It’s expected the tower will be finished and available in October 2020.

Tribal Police Chief Jim Bergstrom shared concern about potential road conditions after a major earthquake hit.

“That’s the idea here, is to put this in place so somebody can walk to it in 15 minutes,” Bergstrom said.

The 15-minute goal is shared statewide as Washington’s Emergency Management Division, which is part of the state’s military department along with the National Guard, embarks on a thorough assessment of the state’s hundreds of miles of vulnerable coast line.

For example, the Ocosta schools sit fairly far down on the peninsula that comprises the town of Westport. It would take another five or six vertical evacuation structures to have one within a 15-minute walk for most residents. That assessment was from Professor Bob Freitag, who has spent years researching vertical evacuation with the College of Built Environments at the University of Washington.

Washington state has a lot of options. In many places tall bluffs come right down to the beach, but the state also includes low-lying peninsulas and other zones. One aptly carries the name Long Beach, which is a long 28-mile stretch of low-lying land forming the state’s southwest coast.

Both the Ocosta school and Shoalwater Bay towers serve as models in both structure and financing. The state already offers a guide on funding towers to encourage more to get built.

“This is our key manual on all the steps you need to take in order to build a tsunami vertical evacuation structure,” said Maximilian Dixon, earthquake program manager at Washington Emergency Management. “It has all the community outreach and how to get the technical partners together.”

Freitag says communities can get creative on their own depending on their economic situation and ability to employ dual use. For example, he says communities could use a resort, hotel, or parking lot.

While Ocosta broke ground as the first place on the continent to establish a way out of the reach of tsunami waves, more structures are coming on line in other states. In Oregon, the new Marine Sciences Building, which is under construction for Oregon State University, will serve a dual purpose role for evacuation.