CALIFORNIA, USA — This story was originally published by CalMatters.

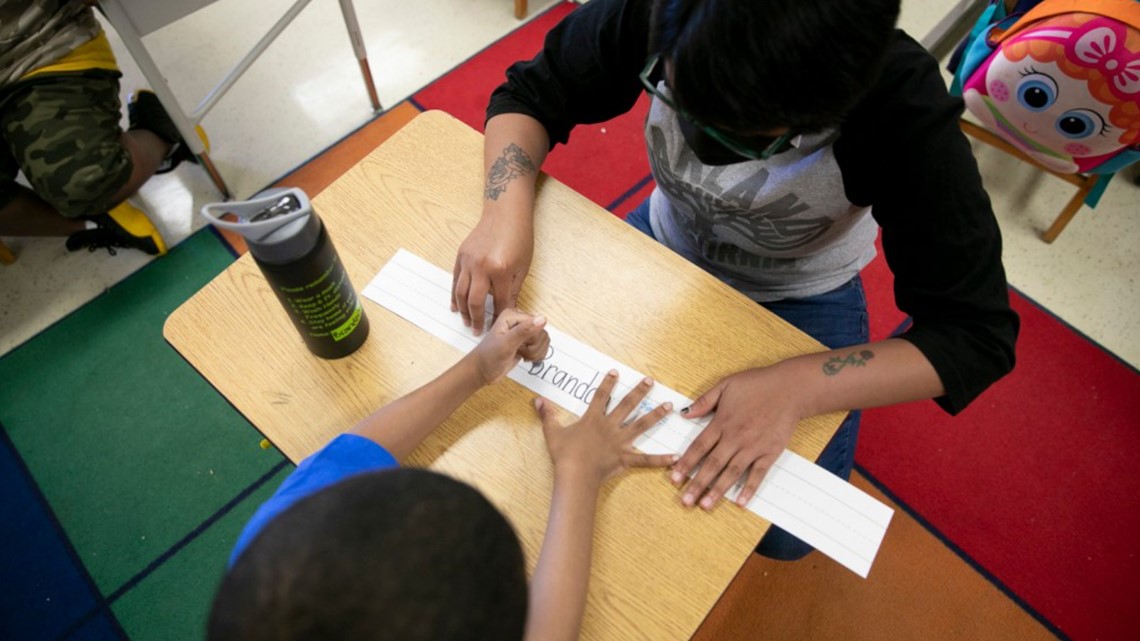

The stakes are high this summer for South Los Angeles parent Renee Bailey. Her daughter Cali just finished kindergarten, but she spent most of it on a computer screen at home where her reading, arithmetic and handwriting skills all declined.

“Overall, it kind of hindered her self confidence,” Bailey said. “We’re hoping to rebuild that so when she goes into first grade she’ll feel comfortable raising her hand.”

Bailey said she will decide whether or not to advance Cali into first grade this fall after seeing how much progress the 5-year-old makes over the summer. Fortunately, Los Angeles Unified is offering in-person summer school to all its students.

Not all California parents will be so lucky.

After 15 months of the pandemic, during which most students learned at home, a spring infusion of $4.6 billion from the state is allowing some districts to increase summer enrollment tenfold. Others are offering it for the first time in years, and even then only to some students.

Staffing was the biggest challenge. Districts statewide have struggled to recruit enough teachers who are willing to work through the summer after an exhausting school year, even with the additional financial incentives.

But whatever their districts are offering, educators statewide agree: Summer school won’t be a panacea to the academic, social and emotional turmoil students have experienced since March 2020.

Big offerings for big districts

Some urban districts like Los Angeles and San Diego Unified, the state’s two largest, are offering in-person summer school to all students. Some summer classes at Los Angeles Unified have filled up, but a district spokeswoman said the district is working to accommodate all students.

At San Diego Unified, a record 22,000 of 98,000 students have enrolled for summer school. Fewer than 3,000 students enrolled for summer school in the summer before the pandemic, according to Nicole DeWitt, an instructional support officer at the district.

The expanded offerings are made possible by the additional $4.6 billion in state funding for summer school, tutoring and mental health services. Most of that money is going to teacher pay. Districts set summer school pay at higher rates to encourage teachers to work through the summer. Districts also needed to hire enough staff to ensure class sizes remain small to prevent the spread of COVID-19 on campuses.

“Summer is a big lift even in a normal year. This year it’s even harder,” said Julie McCalmont, the coordinator for expanded learning programs at Oakland Unified. “We’ve had to hire more teachers and staff. It’s taken us several million dollars more in order to serve these kids.”

Oakland Unified increased its summer school budget by $2 million to $4.7 million this year and enrollment has increased to 6,690 from 4,854 last year. Even so, it has 510 students on a waitlist.

While teachers are exhausted after a grueling school year, some are excited to help so many students transition into the first fully in-person school year since the pandemic first started.

“This opportunity appealed to me because I just think the kids need it this summer,” said Adam Goldstein, a teacher at San Diego Unified. “A lot of them missed out this year, not just on academics, but they missed out on being with other students.”

So far, teachers at San Diego Unified say the preparations for this ambitious summer program have been frustrating. Summer instruction starts on Monday, June 21, but teachers will find out what exactly they’re teaching at training sessions on Thursday and Friday.

But overall, Goldstein has a positive outlook.

“Yes, logistically it’s been a rough rollout,” he said. “But at the end of the day, the kids will show up and we’ll be there for them. I’m not too worried.”

Long road back

No matter how robust the offerings, parents and teachers accept the grim reality that a month or two of summer school won’t undo the damage of 15 months of school closure.

“Summer school is not gonna be a quick fix for the losses students suffered during the pandemic,” said Jenny Hontz, communications director for the parent advocacy group Speak Up based in Los Angeles. “We know online learning was not ideal, particularly for our most vulnerable students. There’s gonna be a huge deficit to make up in the next couple years.”

Even before the pandemic, learning loss over long summer breaks has been a serious problem, especially for low-income students. The governor’s proposed budget asks for $1 billion in additional funding for summer and after-school programs each year for the next five years for districts with high concentrations of low-income students, English Learners and foster children.

Educators say that expanding summer school permanently could do a lot to close the achievement gap.

“If you’re in a privileged area, you’re probably going to be in tutoring and swimming lessons,” said Goldstein, the teacher at San Diego Unified. “In areas of need, you don’t really have access to that. All kids should be able to stay connected to school and friends over the summer.”

McCalmont, the coordinator for expanded learning programs at Oakland Unified, said that for now summer school offerings will remain a compromise. The district, where 72% of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, could only afford to invite the students who need summer school the most.

“Summer learning is never gonna be able to serve everyone who needs it,” she said. “There’s a certain sweet spot. There’s the capacity of staffing, and making sure it’s a high quality program. You have to balance that with student need.”

Rural challenges

Warner Unified, a 200-student rural district in San Diego County, is offering summer school for the first time in years, thanks to the funding from the state. The district invited 44 struggling students to attend. As of June 15, 31 have confirmed. But summer school won’t fix the problems that existed before COVID-19.

Warner Unified has had historically high rates of chronic absenteeism. In the last full school year before the pandemic, 1 of every 10 students missed more than 10% of the school year.

“My first thought was: These kids didn’t even show up during the school year, what’s the chance they’ll show up during the summer? Are they just going to take up a slot?” said Superintendent David MacLeod. “But we have to offer it. It’s worth offering if one kid changes and comes to school.”

Across San Diego County, Poway Unified, which serves a relatively affluent region, is having the opposite problem. While summer school enrollment has increased dramatically, almost 1,300 students are on the waitlist for the district’s non-credit Youth Enrichment Program, which is limited to 555 students and focuses on science, technology, engineering, mathematics and the arts.

The district is also offering a couple of two-week instructional sessions for elementary and middle school for students who have fallen behind. Close to 1,000 students are enrolled for each session with no waitlist.

Poway Unified also enrolled 1,990 high school students who will make-up failed classes, nearly three times its 2019 enrollment. Most of the instruction will be online, but students will be able to be on campus at least once a week for in-person help.

While there are currently 19 students on the waitlist, Poway Unified, which serves about 35,000 students, expects to be able to serve all students who need summer school to make up credits.

Carol Osborne, associate superintendent of learning services at Poway Unified, said staffing the summer programs is the most significant challenge. “Our teachers rightfully need a break,” she said. “When we think about the wellness of our students, we’re also thinking of the wellness of our staff.”

The pandemic’s upending of public education has presented an opportunity to rethink summer school and the traditional academic calendar.

Austin Beutner, outgoing superintendent of Los Angeles Unified, said he unsuccessfully advocated for the state to fund an extended school year to take the pressure off remedial summer school programs.

“I think more time next year would probably be more powerful than summer school this year,” said Beutner. “This is the first time people can be outside. People do need a break.”