SAN DIEGO COUNTY, Calif. — A 44-year-old woman was tested for COVID-19 at the Palomar Medical Center in Escondido. She was found unresponsive in bed three days later while waiting for her results.

In Chula Vista, a 54-year-old man who had been sick for two weeks stayed home rather than seek medical care. His roommate found him on the toilet, deceased.

And an El Centro man with kidney disease was denied dialysis twice after developing a fever and coronavirus symptoms. Days later, he fell out of his car and went to the hospital, where he tested positive for the virus. He was sent home and died soon after at UCSD Medical Center.

These stories reflect the growing number of people in the region who are not getting the medical attention they need until it’s too late.

Deaths at home have climbed to levels well above what San Diego County has seen in the prior three years, according to an inewsource review of public health data. The percentage of deaths occurring in homes — as opposed to in hospitals or other settings — rose from 34.8% in 2019 to about 38% since January.

Andrew Noymer, an epidemiologist at UC Irvine who studies pandemics, said the findings “highlight a gap” in communication from public officials to residents about the virus and when to seek help.

While there’s no way of knowing for sure if a hospital visit will save a life, Noymer said, in some cases, it could.

“People need to understand that if they’re very sick, they need to seek medical care,” he said.

Interviews with healthcare workers, researchers and the families of those who have died shed light on why some who are seriously ill are not going to hospitals: a belief that doctors can't or won't help COVID-19 patients, a lack of education and guidance from public health workers and an ongoing problem with false-negative test results.

Totally alone

Hector Navarro Lopez, who died from the virus after his wife called 911 from their house, hadn’t seen a doctor since 2018.

The 52-year-old San Marcos resident had worked two jobs — in manufacturing and newspaper distribution — to provide for his wife and four children, but it still wasn’t enough. He had let his health insurance lapse for six months to save money.

Noemi Arroyo Ramirez, his wife of 26 years, said he had no underlying health conditions and was almost never sick, so he rarely took the time for routine checkups.

On May 18, after developing a mild cough and difficulty tasting food, Navarro Lopez went to a county lab for a COVID-19 test, his wife said, but he wouldn’t get the results for four days.

In the meantime, he experienced stomach discomfort and an occasional fever. He sought help from North County Health Services in San Marcos, a nonprofit clinic that predominantly serves low-income and Hispanic families.

At the clinic, staff were screening patients for coronavirus symptoms and taking their temperatures before allowing anyone to enter the building.

When Arroyo told the healthcare workers that her husband had a fever the day before, she said the employees abruptly packed up their belongings and retreated inside the clinic. Roughly 10 minutes later, a worker returned, telling the family to go home and wait for a call from a doctor.

Areli, the couple’s oldest child, said it felt like the staff had no compassion for her dad once they thought he might have the virus.

“People don’t know how to handle it,” the 24-year-old said. “They enter this paranoia. There’s no respect.”

She added: “I can’t help but think maybe they didn’t do enough.”

The ailing father received a phone call later that day from the clinic. Arroyo said the doctor didn’t ask to see her husband’s stomach over video chat and offered no medication or treatments — only instructions to call back once Navarro Lopez’s test results came in.

The following day, on May 22, he got the news: positive for COVID-19.

Arroyo called the clinic and left a message, she said, but never heard back.

In a statement, Dr. Marie Russell, the North County Health Services chief medical officer, said its clinics have been “committed to caring for the community throughout the COVID-19 pandemic,” and began screening patients for symptoms early on to protect others from the virus.

Russell said if someone tests positive at their designated labs, a doctor will follow up and provide care instructions. But in Navarro Lopez’s case, he was tested at a different lab before he ever walked into the San Marcos clinic.

A spokesperson for the clinic added that its doctors strive to do video appointments when they can’t see patients in person, but sometimes phone visits are necessary if there are technical difficulties or the patient has “limited video capability.”

Arroyo said she was left to care for her husband using her own intuition, television and Google search results.

She gave him hot tea, isolated him in a bedroom, took his temperature multiple times a day and supplied him with aspirin, vitamin C and Tylenol.

But Arroyo is no doctor. She didn’t know that the coronavirus can cause oxygen levels to drop dangerously low even while someone looks and acts normal.

And she didn’t know what to do when her husband’s fever rose to 103 degrees. All she saw in online articles was to go to the hospital if your temperature reaches 104.

“It felt like, ‘This is your patient. Take care of him. It’s your responsibility. If he passes away, it’s your fault,’” Arroyo said.

“I felt like that, like I’m alone. Totally alone.”

Arroyo said after losing her husband to COVID-19, she lost her trust in healthcare providers, too.

“If I feel like I will die, I will go to the hospital,” she said. “Otherwise, I will not go to a hospital or talk to a doctor because they don’t help me with something simple (like) stomach problems.”

A devastating outcome

Reports from the San Diego County medical examiner’s office tell the stories of more than a dozen COVID-19 victims since March who died at home or on their way to hospitals.

In five cases, the victims tried to seek medical care in their final hours before death but could not be saved. In another four, they were rushed across the border from Mexico in search of an ambulance. In three, they suffered serious falls — a common side effect of the virus in old age — that resulted in their deaths.

Four other reports say the deceased were found unresponsive at home by family members, roommates or others.

The medical examiner’s office only reviews a small fraction of COVID-19 cases, including sometimes when the cause of death is unclear or when the victim hasn’t sought medical care recently. The reports grimly describe how the virus can attack the body at full force without warning, and how quickly it can take a life — especially when medical professionals aren’t available to help.

Experts say a reticence to seek medical care can result from misunderstandings about how American hospitals are operating during the pandemic.

This is especially true in border communities. Dr. Eva Tovar Hirashima, the prehospital medical director at the Tijuana Red Cross and an emergency room doctor in Riverside, said people who have previously sought medical care in Mexico may expect a similar experience in the U.S. — that hospitals are too overwhelmed to take care of patients who aren’t visibly, seriously ill.

“People who are first generation (Americans) and who have been exposed to the Mexican medical system may believe that in order for them to actually be assessed appropriately and admitted to the hospital, they really need to come at the last minute,” Tovar Hirashima said.

“Because if they don't come at the last minute, then they'll be discharged home.”

Early on in the pandemic, Tovar Hirashima realized that more Tijuana residents asking for medical help from the Red Cross were dead by the time emergency paramedic teams arrived on the scene.

San Diego physicians noticed something similar on the U.S. side of the border — the number of emergency room patients was shrinking, not growing.

County data shows that early on in the pandemic, roughly 48,000 fewer people visited the region’s emergency rooms than during that time in 2019.

Meanwhile, home deaths started to rise. Hundreds of more people in San Diego County have died in their homes than would be expected in a normal year, according to a review of county public health data.

By April, hospital executives were appealing to the public through the news media, encouraging people to seek medical attention if they felt unwell.

“Our concern is the patients that do have chest pain or stroke symptoms — if they’re waiting to come in, time is literally ticking away,” Dr. Ghazala Sharieff, the chief medical officer of Scripps Health, told KUSI News in April. “So if they wait, that could be a devastating outcome.”

Dr. Wilma Wooten, the county’s public health officer, said officials are educating the public through their healthcare partners, media sources and other channels to alleviate concerns about the coronavirus. She encouraged residents to reach out to their physicians if they don’t feel well.

“Don't be afraid to seek healthcare,” Wooten said. “Call your doctor. Much of medical care is being conducted via telemedicine. So in many cases you may not need to go in face-to-face.”

But Wooten’s statement didn’t acknowledge the many San Diegans without a regular primary care physician to call. Navarro Lopez, the San Marcos resident, was one of them.

In county survey results from 2015, about 14% of San Diegans said they did not have a regular place to go when they became sick, and 18% had not visited a doctor in the past year.

Gene Kallenberg, a faculty physician at UC San Diego, said primary care doctors are a key source of support and guidance for COVID-19 patients. Not having one is frequently the root of the problem, he said.

“Potentially the absence of a relationship with a primary care physician led to the patients making these poor judgments that left them home in bed and dying,” Kallenberg said.

At UCSD, doctors communicate with their coronavirus patients almost every day until they recover, Kallenberg said.

“It's tragic to me when someone has no one to call,” he said.

Playing catch-up

If a resident with COVID-19 doesn’t have a regular primary care provider, the county tries to fill in the gap.

The county public health office says it has multiple “touchpoints” to communicate with coronavirus-positive residents and provide them with care instructions.

But some people — like Navarro Lopez and his family — get left behind.

The first point of contact occurs when a person tests positive for the virus at a public lab. A county nurse is supposed to reach out to them with instructions for isolating at home, wearing a mask, social distancing and disinfecting their environment. The nurse is also supposed to explain when it might be necessary to go to the hospital.

Arroyo said her husband was tested at a county-run lab in Escondido, and yet the family never received a call.

The second touchpoint occurs during contact tracing. Public officials say case investigators try to reach everyone who tests positive for COVID-19 so they can track down others who were potentially exposed. Then, a separate group of workers called contact tracers reach out to those who may have been infected.

The process poses another opportunity for the public to speak with experts about what they should do to protect themselves and monitor their health. But Arroyo said she and her husband did not receive calls from investigators or contact tracers.

County Supervisor Nathan Fletcher, who co-chairs the region’s COVID-19 taskforce, said he didn’t know the details of Navarro Lopez’s case, but it’s possible the county could have had outdated or incorrect phone numbers for the family.

Rick Greenwood, a member of California’s testing taskforce, said case investigators and contact tracers up and down the state are swamped with work. The problem with contact tracing, he said, is the more tests that are conducted, the more the staff becomes overwhelmed.

“If you only do a thousand tests and find a few people positive, the system isn't stressed,” Greenwood said. “If you start doing 200,000 and 300,000 a day and end up with thousands of positives, you need to have a system in place to know what to do with them.”

“The state’s playing catch up,” he added, “trying to hire people at the same time that hundreds of positive tests are coming in.”

In San Diego County, contact tracing efforts slowed in late July. At the time, the county’s goal was for 70% of investigations to begin within 24 hours, but only 11% did.

Fletcher said the county has hired additional staff and now has a big enough team to reach everyone who has tested positive and the people they could have infected.

As of late August, 97% of investigations are opened within one day, and more than 40,000 investigations have been performed, public health data shows.

“The aim and intention is to contact all,” the supervisor said. “And that's how we're structured. That's how we're staffed. That's how we're set up. And that's how we're operating.”

Of the people local investigators reach out to, 90% have provided information to the contact tracing team. That leaves 10% — or 3,472 people — who could not be reached or would not answer questions as of mid-August, including Navarro Lopez’s family.

With no experts to turn to for advice, Navarro Lopez’s wife didn’t seek medical attention for him until she knew it was an emergency.

On the morning of May 27, her husband told her something was wrong with his legs.

“I feel bad. I feel bad,” Navarro Lopez repeated.

Arroyo called 911, but by the time an ambulance arrived her husband insisted he was better and didn’t want to go to the hospital.

She begged.

Arroyo told her husband this might be their one chance to finally hear from a healthcare worker about his illness and how she should be taking care of him.

Navarro Lopez obliged his wife’s pleas, walking to the stretcher. He had two heart attacks before he made it to Palomar hospital.

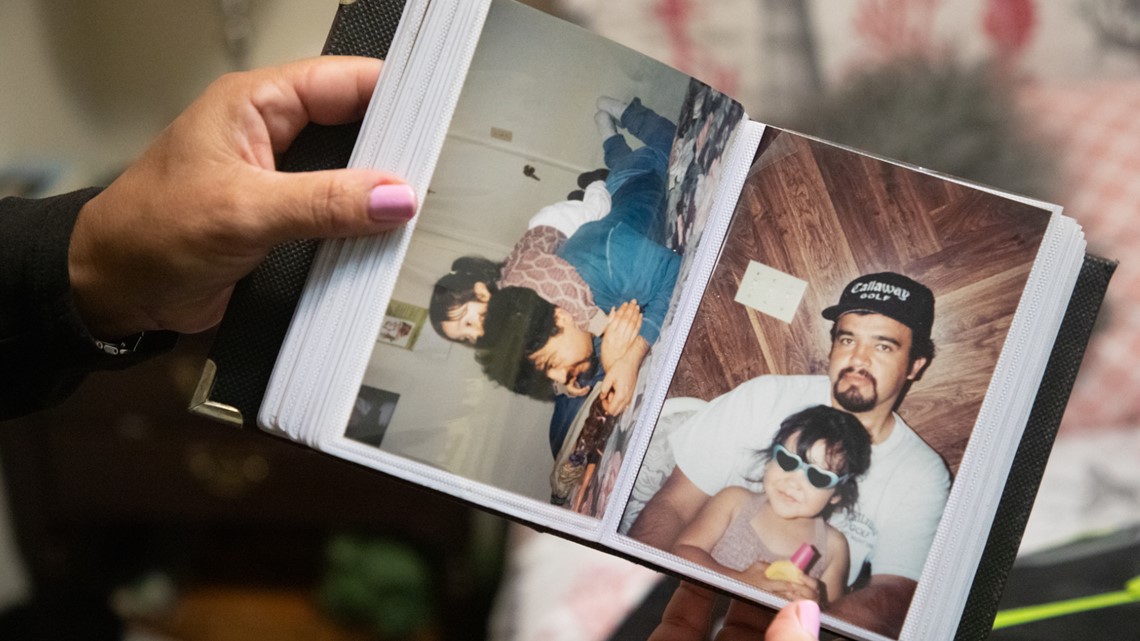

The day he died, Navarro Lopez left behind a son finishing ninth grade, a daughter graduating high school in two weeks, a son in college with dreams of working in the Sheriff’s Department and a 24-year-old daughter less than two months away from getting married.

The family’s cozy San Marcos home is copiously decorated with sports trophies, framed photos, school awards, woodworking projects and religious icons. Gathered together there in late July, Navarro Lopez’s four children and their mom held each other close, crying and laughing as they remembered their beloved patriarch.

“We're gonna use my father as something that's going to propel us forward and for us to succeed,” said Hector, 22.

Miranda, 17, called her dad a “man above all men” with a pure heart. Axel, 15, said nobody ever had anything bad to say about his father.

Areli, 24, described her father as a quiet man who protected and guided the family.

“I knew that with him and my mom around as our parents, everything was going to be OK and everything was going to be possible,” she said.

The loss taught her that sometimes the only way to survive is to be resourceful, Areli said.

“If somebody doesn’t want to help you, find a way to help yourself.”

Testing the system

Alfonso Ye Jr., a 25-year-old part-time pharmacy technician, tried to get help when he started feeling sick.

On March 17, he went to Scripps Memorial Hospital in San Diego and tested negative for the virus, according to coroner’s records. The hospital diagnosed him with a respiratory infection and gave him no medication, the records say.

Not long after his discharge, the El Cajon resident headed to Riverside County to stay at his mom’s house in La Quinta until he felt better.

Eight days later, when he had trouble breathing, his mother wanted him to go to the hospital, according to the coroner’s records, but Ye repeatedly said his COVID-19 test was negative and did not go.

Yes, mom called 911. The paramedics couldn’t save him.

A posthumous test confirmed the pharmacy student was positive for the coronavirus. The coroner’s records said he died from respiratory distress caused by COVID-19, making him one of the first documented San Diego County residents to die from the virus.

Tools to detect the coronavirus aren’t advanced enough to decipher whether someone like Ye developed the virus after testing negative or if his first test result was inaccurate.

As the number of COVID-19 tests conducted continues to rise, so do the number of false-negative results, which can discourage someone from seeking potentially life-saving medical care.

A June paper from the Mayo Clinic estimated there could be more than 20,000 people in California who received false-negative results. The scientists warned that if healthcare providers aren’t careful in interpreting test results and advising patients, it could cause someone to develop a dangerous confidence that they are virus-free.

Research from Johns Hopkins found that COVID-19 tests working at their best still lead to false negatives about 20% of the time, meaning at least 1 in 5 people with the virus receive negative test results.

The Food and Drug Administration cautions healthcare providers that false-negative tests can lead to a delayed diagnosis and improper treatment. Plus, they can result in patients failing to monitor their symptoms closely.

In a June fact sheet, the federal agency advised that when a patient tests negative, medical workers should consider the likelihood that the person was exposed to the virus when deciding how reliable the test results are.

In Ye’s case, he had a colleague who had recently tested positive for the virus and was on a ventilator, according to what his mother told the coroner’s office.

A spokesperson for Scripps Health declined an interview request and did not comment specifically on Ye or his test results. He said the hospital system has no way of knowing how often negative COVID-19 tests are tied to individuals who later test positive.

Ye’s death was a loss upon loss for his family. His father, of the same name, died about two years ago.

Stephanie Silva, Ye Jr.’s cousin, said Ye was very ambitious and his life was going well. He loved his job and was planning to graduate from the pharmacy program at Pima Medical Institute in Chula Vista in April. He was living in El Cajon with a roommate, his first time venturing away from home in a big way.

Ye loved San Diego’s live-music scene and Disneyland, his cousin said. He was someone people always looked forward to seeing and someone who’d go out of his way to visit friends and family.

“He was always the go-to person for anyone that wanted to just talk,” Silva said. “He was the person that you wanted to talk to if you were feeling sad.”

Ye was well liked and high achieving. He’d applied for and earned his pharmacy technician license while still in school, a step that showed his initiative, said Benjamin Montoya, one of his professors.

“He was young. He was full of life,” Montoya said. “He had so much in front of him. It really hit me hard.”

It’s been almost six months since Silva lost her cousin. She said his death and the other lives lost to the pandemic feel like they could have been avoided if more safety precautions had been in place.

“It’s very sad how many people see these numbers but don’t really see the people behind them,” she said.

inewsource intern Sofía Mejías-Pascoe and reporter Camille von Kaenel contributed to this story.